Allocating Art & Science

- Ryan Bunn

- Jul 1, 2024

- 4 min read

Allocating, like investing, is both art and science — The science continues to evolve — Warren Buffett’s teachings apply as much to allocators as investors.

ALLOCATOR ART & SCIENCE

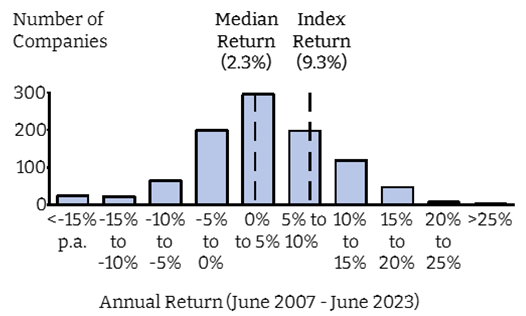

As discussed previously, active management continues to lack a scientifically proven edge, instead relying on the art of investing to justify the industry’s existence. Asset allocators believing in active management face a similarly disheartening challenge, scientifically speaking, in selecting outperforming managers. Just as active managers face the challenge of selecting stocks in a world where median returns are worse than the average, asset allocators must select from active managers knowing that most will underperform, particularly once fees are included.

Fortunately, asset allocators can leverage the same principles advocated by investment artists when performing their manager searches.

Concentration or Punch Card Investing

Allocators should consider Warren Buffett’s “punch card” advice to limit their selection of active managers just as these managers limit their stock selections. The rationale behind the punch card is to focus, and invest in, only truly outstanding investment ideas and managers. Because of skewed investment returns, and correspondingly skewed manager performance, most active managers will underperform. This does not invalidate the entire active management industry, but instead encourages allocators to raise their standards and invest with only the best.

Fortunately, due to the range of passive investment options, implementing this approach is potentially easier for an allocator than an active manager. Allocators should not only evaluate active managers versus other competing managers, but also against available passive options for the asset class. This seemingly commonsense approach is often ignored though, as the choice between active and passive management frequently occurs at the beginning of a search as opposed to the end!

This practice can be applied to an allocator’s existing managers as well. Given most managers underperform, any indication that an active manager’s process is deteriorating should be promptly addressed. If an active manager is not demonstrably outstanding, allocators should act, replace this manager with a passive option, then patiently wait until using their next “punch” on a new manager.

The Bottom Decile or Don’t Lose Money

Investment artists apply the “don’t lose money” principle by designing their processes to avoid bottom decile investments. This provides allocators with a surprisingly simple method of identifying managers that truly understand the value of preserving capital.

Underperforming managers lose because of large drawdowns from individual positions. A pattern of blowups is deeply revealing regardless of the idiosyncratic issue that occurred, perceived intrinsic value of the position (and likely growing “upside”), or broader market performance during the disaster. Naturally, due to the random nature of stock returns, every manager will, over time, own a bottom decile stock or two, but this should be limited to less than 10% of investments (it is the bottom decile of course). Managers with above average allocations to bottom decile investments, even if they are outperforming overall, reveal themselves as return-seeking, high-risk investors.

An allocator can also implement this risk-first mindset and design their processes to avoid managers that could end up in the bottom percentiles. Avoiding the worst active managers, like avoiding the worst stocks, is a clear path to portfolio alpha. This mindset requires the discipline to live a mundane existence as the most exciting, and volatile, investment strategies must be strictly avoided.

Market Timing or Hold Cash

The investment world abhors cash due to a fallacy regarding both its opportunity cost as well as investors’ ability to time the markets. Allocators can improve their results by moving beyond these fallacies.

If an allocator is following the “punch card” and “don’t lose money” principles, they have assembled a roster of high-quality active managers. Why constrain these highly vetted managers? Expanding (not eliminating) cash limits poses only a minor risk to portfolio performance, particularly for diversified portfolios, and provides managers with an additional tool to generate alpha. The ability to monitor an active manager’s use of cash also provides critical data for evaluation – how many “value investors” stood pat in 2020 while Warren Buffett invested heavily in his own shares? If an active manager turns the flexibility of holding cash into a drag on returns it is the manager’s value that should be questioned, not the allocator’s decision to provide investment flexibility.

Allocator Market Timing

Allocators should hold cash as well. Replacing a marginal, fee-charging active manager with interest-bearing treasuries can enhance portfolio returns, particularly if the cash is eventually allocated to a non-marginal active manager in the future, ideally in a down market.

How is an allocator to know when the down market has arrived? Just look at your alternative holdings! When public markets are overvalued, venture capital and private equity owners race to IPO. When the public markets are cheap, these IPOs dry up. This is market timing.

Cash allows can allocator to counter-balance their market-timing alternatives, ideally allocating to public markets in times of limited IPO activity.

Extreme Allocation

For allocators constructing durable, diversified portfolios, extreme is not an attractive adjective. Underneath a prudently built portfolio though, non-linear stock return dynamics will ultimately impact an allocator’s returns. Because of this, allocators should appreciate the extreme, tail events that will differentiate their performance by concentrating on only the most outstanding active managers, monitoring and culling managers that frequently own extreme underperformers, and adopting the “extreme” view that cash holdings are a strategic tool as opposed to a return drag.

While Warren Buffett is often viewed as an investment artist, he may more accurately be characterized as an allocation artist. While he does make direct investing decisions, he ultimately allocates between cash, public investment holdings, and alternative, private investments. Given his propensity to praise passive investing, to the dismay of many active managers, maybe he’s been speaking to allocators all along!